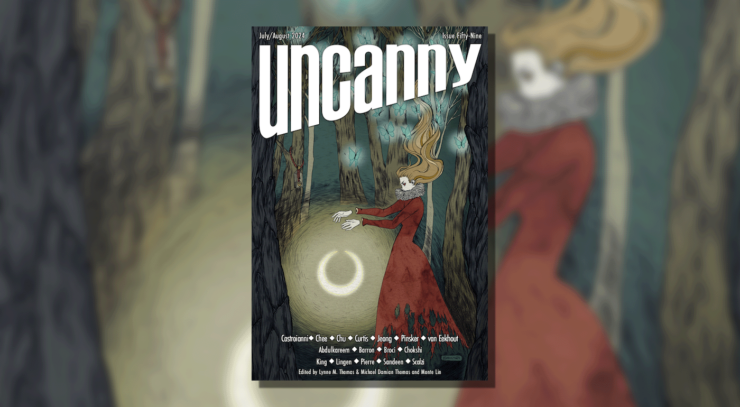

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover Greg van Eekhout’s “Across the Street,” first published in July 2024 in Uncanny Magazine. Spoilers ahead!

The story’s narrator likens himself to Moby Dick’s Ishmael: He too has endured “damp, drizzly Novembers” of the soul, during which he must fight the urge to step into the street and knock off people’s hats. Ishmael could shake his doldrums by returning to the sea, but narrator’s lunch break is too short to allow for whaling voyages to the south seas. He can only walk around the same old block, stopping at Starbucks and then pacing by the usual American medley of megastores and fast food chains before arriving back at his office and spreadsheets.

This particular day, the narrator’s “very deep in a hat-knocking mood,” so he crosses the street.

A few blocks along, he finds a turtle garden he’s never noticed before. Small turtles swim in a sparkling pond bordered by cobblestones. “Free from the cubicle where [his] sense of adventure atrophies,” he crosses another street.

Here the pavement bears prints pressed into it when its cement was wet. They look like they were made by huge clawed human hands. The prints are stained red. Narrator does love a “touch of civic whimsy.” The street signs are in a language whose alphabet he doesn’t recognize. Maybe he’ll find a new ethnic restaurant! He’s not “self-destructive” enough to explore that creepy antique doll shop, but when a voice squawks “Enter” from a pet shop door, he must obey. Inside are the usual bettas in cups, parakeets, mice and rats and hamsters, but there’s also a four-inch dragon working its stubby wings and coughing smoke. “You’re doing great,” narrator encourages it. He’d never see a baby dragon in the company cafeteria.

He crosses another street. He passes a record shop playing a song he vaguely remembers. He hums the tune, mutters some lyrics, then the complete song comes to him. His walk turns jaunty, his face relaxes. He stands on a corner among six other people tapping their feet and each singing a different song. When the light turns green, they go their separate ways.

Across the street the alphabet changes again, and glyphs draw narrator along. Down a manhole, a head surfaces from dark water. Its face is human, its eyes alien, “ancient and dark as starless space.” Held by its gaze, narrator feels the patience necessary to “lay low until the new, boiling sea grows cool enough to support ocean prey.”

The creature vanishes. Narrator next notices a meat shop displaying flayed human corpses. He doesn’t care for this “sketchy” neighborhood and wonders if he should head back. But he still feels like knocking off hats, so he crosses another street.

Here the streets are named things like “The World is a Sphere but Time is Linear Avenue.” He enters a church so old its corners are weathered soft. Inside, figures holding paper cups sit on folding chairs before the altar. Each has six wings: a pair each crossing feet, back, and face. One says, “Hi. My name is Zerachiel, and I’m an alco–” Then the figures notice narrator and withdraw their face wings to reveal angels’ eyes. Narrator weeps with awe and rushes out, apologizing for his intrusion.

Parking meters tell car owners how much longer they’ll live. Narrator would like to help a sniffling man, but the meters won’t take his quarters. Again he crosses the street. The Starbucks here has a logo like the manhole creature, and its customers are on their knees, clutching their stomachs and choking. He decides against buying another latte. He starts to cross once more, but sees on the other side a spiraling vortex like a horizontal tornado. The pressure differential feels more than his brittle skull can endure. There’s a noise his “brain has not evolved to process.”

A woman in jogging clothes and a pink baseball cap stands beside him. “Is that a portal?” narrator asks. Everything’s a portal, she replies. Every wound, every conversation, every passing second. More specifically, the one across the street leads to “what happens when you go too far. The great unraveling… Demolition and rebirth but no return.”

When the light turns green, narrator asks if the woman’s going to cross. She was going to, but now she hears “the shriek of gods burning on their pyres.” Hell no.

Narrator thinks the woman seems smart. But because he has an urge to smack off her baseball cap, he steps “into the howling.”

What’s Cyclopean: It’s amazing what you can find once you’re free of the cubicle where you’ve been “incarcerated inside spreadsheet cells.”

Libronomicon: Moby Dick references! Everywhere!

Weirdbuilding: Across the street, so many potential stories beckon. Perhaps you’d like to take a detour into the creepy doll shop?

Anne’s Commentary

When the woman in the pink baseball cap claims that everything’s a portal, she’s not exaggerating, at least as far as speculative lit genres are concerned. So much spec-lit contains portals—technological or magical openings into Other Places, Realities, Dimensions, Realms—that to list a fraction here would eat up my entire word allotment. Should you feel like making a to-read list, Goodreads provides one of 355 portal fantasies.

Just last week, we encountered a tangle of downed trees portalling a real-world pet sematary and a burial ground for both humans and companion animals, not all of which necessarily remain buried. “Deadfall” is a good name for Stephen King’s barrier between realities. Besides a snarl of decaying vegetation, “deadfall” can refer to a trap designed to drop a crushing weight on prey. It’s this second definition that might apply to the seemingly innocuous crossings van Eekhout’s narrator (let’s call him neo-Ishmael) makes. We all cross streets, right? How else are we, like the chicken and Church the Cat, going to get to the other side?

But not all crossings are advisable.

Still, no crossing ventured, no turtle gardens or new ethnic restaurants, no baby dragons or angelic AA meetings discovered. When one’s spiritual November is the product of toxic ennui, one can either knock off some hats and then be bored in jail or one can ditch the too well-beaten path and take some risks. Sign up to hunt the great leviathans already! Or at least boldly go where no lunchtime stroll has led you before.

Neo-Ishmael’s alternative is to meekly return to the cubicle where his “sense of adventure atrophies.”

In his Uncanny Magazine interview with Caroline M. Yoachim, van Eekhout says that he’s “mostly just trying to make the ordinary seem strange and the strange seem ordinary.” This, he continues, is a paraphrase of something the poet Novalis wrote. The verbatim quote is:

To romanticize the world is to make us aware of the magic, mystery and wonder of the world; it is to educate the senses to see the ordinary as extraordinary, the familiar as strange, the mundane as sacred, the finite as infinite.

Novalis (1772-1801), who was influential in the German branch of the Romantic Movement, defines the aims of that reaction to the Industrial Revolution with admirable conciseness. And what better 21st century emblems of said Revolution than the cubicle in which Neo-Ishmael languishes, and the homogenized soullessness of his lunchtime perambulations? This boy needs to trash the iced grande vanilla latte and get some romanticization! Luckily, he exists in such close quarters to magic, mystery and wonder that all he has to do is cross a street to begin his journey into the extraordinary, strange, sacred and infinite. And all he has to do to hit portals on each crossing is to be in a deep enough November mood to reject the ordinary, familiar, mundane, and finite.

To reject them once and for all, maybe.

In the linked interview, Yoachim asks van Eekhout which of neo-Ishmael’s “streets” he’d cross himself. Van Eekhout opts for the turtle garden. As the weirdness and danger increase with each crossing, and “turtle garden” comes first, it’s the safest choice. It’d be hard to maintain a turtle pond in a busy urban setting, but it could happen. Next come the huge and clawed human footprints preserved in pavement cement. Such creature being impossible, Neo-Ishmael writes them off as a bit of “civic whimsy” and the red stains within them as paint or rust rather than, um, dried blood.

Neo-Ishmael grows more habituated to wonder, more credulous, the farther he goes from his routine routes. A baby dragon in a pet store becomes an unusual rather than an impossible sighting. Six people performing impromptu street-corner a cappella, each singing a different song picked up in passing a record shop? That’s a soft drink ad, not real urban life, but why argue with such a feel-good moment?

The next streets start getting scary weird, or so people not progressively numbed to weirdness would feel. There are more signs in unknown scripts and mandalas so compelling that Neo-Ishmael feels he’s been staring at them for ages, but his only worry is that he may be late returning to work. Down in the sewers swims not the flushed alligators of urban legend but a merperson with eyes as “ancient and dark as starless space.” A meat shop displays butchered human corpses. Neo-Ishmael neither thinks he’s stumbled on a slasher movie set nor recoils in horror; he merely supposes he’s wandered into a “sketchy” neighborhood and crosses another street.

Here his habituation has progressed so much that he can read the street signs, which are all about cosmology and quantum physics. In a time-weathered church, six-winged figures participate in an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting complete with folding chairs and coffee. Noticing an intruder, they reveal the eyes of seraphim and burst into flame. Finally Neo-Ishmael screams with awe at the familiar gone strange, the mundane sacred.

The next street’s Starbucks has replaced its logo with the sewer creature. All its customers are choking. This version has Neo-Ishmael ready to cross without further exploration, but a vortex blocks passage. Shifting pressure lances his ears. Fortunately, the jogger sharing his street corner knows what lies behind the vortex-portal. All things are portals according to her, but this one is the crossing too far, the ultimate beyond, reality unzipped, demolition, rebirth without return, pick your favorite metaphor. You can only know by going within.

Going within sounds like passing from the finite to the infinite, Novalis’s last stage of world-romanticization. The jogger’s not crossing this street; that noise the vortex emits? It’s the “shriek of gods burning alive on their pyres.” Who needs that kind of routine-breaker?

Neo-Ishmael does, because in spite of all he’s experienced, he still wants to knock off the jogger’s cap. Who needs that degree of world-weariness? Besides, portals exist to be entered. The Beyond, once broached, becomes an irresistible lure.

Didn’t Last Exit teach us that?

Okay, Neo-Ish. Say hi to the burning gods for me.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Call me Ishmael! ‘Cause I mail people about Ish-ues? No, that doesn’t work at all. (I may be a bit punchy this week from dayjob deadlines.) Because I am pretty much always guaranteed to squee at a Moby Dick reference, though, that’s a good reason. I adore a long, rambling book about how god keeps trying to create new Jonah prophets until one actually follows commands instead of running away and getting eaten by a fish, and about whales (incorrect answers only), and about marrying a guy you just met and worshipping at his altar because Golden Rule. And about how to handle that feeling when the world wears so badly at your brain that you just want to knock people’s hats off.

Ishmael, as van Eekhout’s narrator admits, has the advantage of being able to go to sea and let the overwhelming power of the ocean smooth out those rough edges. Hard to do on a 45-minute lunch break—and worse yet, a spreadsheet-heavy job with a 45-minute lunch break is likely to exacerbate that hat-knocking mood.

Fortunately for Neo-Ish, awe-inspiring vastness can be found ashore. Sometimes, just by exploring a block you’ve never walked before. Maybe hat-knocking desires push you to turn in novel directions that aren’t otherwise available. Why not? If going to sea can put you in the thrall of a maltheistic ex-prophet, anything’s possible. The wild and awesome is wherever you need to find it.

Unfortunately for Neo-Ish, this particular mood is such as to keep one turning and turning in widening gyres increasingly weird directions. Little pond full of teeny turtles, that’s great. My kid, at 3, encountered turtles for the first time at an aquarium and clearly thought that they were an unusual variety of beetle. Tiny dragon in a pet shop, I want to see it and so does my beetle-turtle-loving kid. You could bring it back to the office and point that smoking nose at your paperwork. Aeons-patient sewer Deep Ones seem worth a conversation, if they’re willing to take a shower first.

Church-going angels without even the etiquette to say “FEAR NOT,” on the other hand, we can all do without. And it only gets worse from there: I personally am going back the way I came when I hit the extremely-not-kosher cannibalistic butcher shop window, no matter how many hats I need to knock in the course of retracing my steps.

This is apparently part of an informal series of van Eekhout shorts about urban weirdness, and I hope to find more of them. In the meantime, it reminds me of Neil Gaiman’s Walking Tour of the Shambles, a strange little chapbook describing a self-guided tour of a somewhat unusual Chicago neighborhood. Some of the stores even have an online presence. It’s the matter-of-fact descriptions, the straightforward interactions, the willingness to move on from the current once-in-a-lifetime-and-beyond experience to the next one without pausing to stare, that seem familiar in this week’s selection. That and the risk of getting pulled into a portal and failing to return from whence you came, so make sure your parking meter’s topped off before you head out.

Come to that, it’s a risk for the crew of the Pequod as well. Only I survive to tell, etc. Just because you’re god-hunting doesn’t mean you can forget to bring in the oil from the lesser demi-gods who populate these vasty deeps. Or to replace your melted shake.

Not at the Temple of Dagon Starbucks, though.

Pet Semetary’s been reminding us, these past weeks, that some barriers aren’t meant to be crossed. It’s also been reminding us that humans, being humans, are likely to find reasons to cross them anyway. And if that doesn’t jar us out of our doomscrolling, another barrier, and another, until any alternative is far behind.

What happens after that? Well, some stories start when you step off into the howling, and some end there. But Ishmael the First would warn you that hat-knocking humans is a slippery slope to hat-knocking deities. At that point, the shriek of gods burning alive on their pyres might be just what the doctor ordered.

Next week, what happens in the burial ground doesn’t stay in the burial ground in Chapters 23-25 of Pet Sematary.

This is so wild, but in early 2016 I went for a walk on my lunch break to a neighborhood where none of the homes had stylistic consistency, and even the sidewalk was a kind of patchwork of different styles. Like, there was an abandoned Chinese grocery next to a McMansion, next to a Frank Lloyd Wright-style ranch with security cameras everywhere, next to a little cottage with a fruit tree. I had the sense that I’d wandered into God’s “spare parts” lot, and imagined I might see, I dunno, a fleet of inanimate humans waiting to be wound up and set into the dollhouse of the world.

I even thought the street should be called Miloscrzemioslo, a Polish transliteration of Lovecraft and a nod to my hometown’s Polish heritage.

I never wrote the story. But I think Greg Van Eekhout kind of wrote it for me!

Makes me feel like the story was floating around trying to get told.

The angels in the church match the description in Isaiah 6:2.